Elders

Eternal Blue Sky: A Mongolian Shaman On The Language Of Nature (video)

Unprecedented Conversations: Altai Elder Danil Mamyev speaks at Jeju, IUCN 2012, South Korea (video)

Unprecedented Conversations: Kyrgyz Elder Zhaparkul Ata (video)

Pana and Awakening in the Earth Changes (video)

Traditional Hawaiian Healer Kapi`ioho Lyons Naone speaks about “Uli” (video)

Zulu Necklace of Mysteries (video)

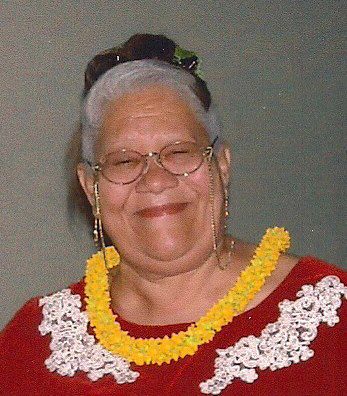

A Conversation With Mahilani Poepoe: Hawaiian Kupuna and La`au Lapa`au (video)

Successful Teaching of Ancestral Tribal Knowledge (PDF)

Apela Colorado PhD, Elder

272-2 Pualai St.

Lahaina, Maui, HI.

96761

17 Feb. ’00

Greetings return to you, Apela, and to the Elders (grandmothers) present, and especially to the loyal members of the TKN, in the love and in the light of the ancestors, The Source of Life.

Aloha Kakou!

I am in awe from yesterdays moving performance of sharing, by your humble, reverent, and loyal students of life; good work Apela! I was especially moved by Martina’s ancestral song of honor and all of the beautiful giveaways and story telling

. Thank you Apela for another beautiful day in paradise. I am greatly honored.

Each of those students in this group is striving to use, digest, and diversify the information into the channels of their mind, body, spirit, complex without distortion. The few whom they will illuminate by sharing their light, are far more than enough reason for the greatest possible effort. To serve one is to serve all.

Therefore to teach/learn or learn/teach, there is nothing else which is of aid in demonstrating the original thought (love) except their very being, and the distortions that come from the un-explained, inarticulate, or mystery-clad being are many.

Thus, to attempt to discern and weave their way through as many group mind/body/spirit distortions as possible among their peoples in the course of their teaching is a very good effort to make. I can speak no more valiantly of their desire to serve.

Again, Mahalo nui loa to the Elders (grandmothers) present, to all the students resonating and radiating to the light of the ancestors, and to those who came to observe the clarity of your teachings of the ancestral Tribal Knowledge.

With the permission of the ancestors, I leave all of you in the love and in the light of the ancestors; rejoicing in the power and the peace braided with the cords of patience revealing the tapestry of:

LOVE ALL THAT YOU SEE,

LIVE ALL THAT YOU FEEL,

KNOW ALL THAT YOU POSSESS.

Respectfully, in Service

Hale Makua

Hono Ele Makua

(Council of Elders)

Weaving the Way of Wyrd (PDF)

Weaving the Way of Wyrd: An Interview with Brian Bates

by Janet Allen-Coombe

Brian Bates, author of The Way of Wyrd and The Way of the Actor, is the leading exponent of a movement that seeks to revitalize Europe’s ancient shamanic traditions. Working from a scholarly and experiential approach, he has developed a contemporary shamanic practice based on the original Anglo-Saxon and Celtic traditions as documented in historical texts, art, and literature.

Born and raised in England, Bates lived in the United States during the 1960s. After earning his doctorate in psychology from the University of Oregon, he returned to England to serve as Research Fellow at King’s College, Cambridge. He currently teaches courses in shamanic consciousness and transpersonal psychology at the University of Sussex, where he also directs the Shaman Research Project. In addition to his academic career, Bates directs plays in London, teaches shamanic workshops for actors, and leads experiential courses in European shamanism.

Bates is perhaps best known for his historical novel, The Way of Wyrd, which documents in fictional form his research on ancient European shamanic practices. Recently released in paperback by Harper San Francisco, the book provides a fascinating narrative about Anglo-Saxon shamanism—and serves as a focal point for the following interview.

Janet Allen-Coombe: Wyrd is described in many ways in your book, The Way of Wyrd. Would you explain what word is?

Brian Bates: The term word is the original form of today’s weird, which means strange or unexplainable. Wyrd had essentially the same meaning more than a thousand years ago in shamanic Europe, but in sacred rather than mundane realms. Wyrd was the unexplainable force—the great mystery underlying all of existence—that was the cornerstone of Anglo-Saxon shamanic practices.

The essence of wyrd is that the universe exists within polarities of forces, rather like the Eastern concepts of yin and yang. according to Anglo-Saxon beliefs, the universe originally consisted of two mighty, unimaginably vast force regions—one of fire, the other of ice. When the fire and ice met, they exploded, creating a great mist charged with magic force and vitality.

This “mist of knowledge” exists beyond time, concealing wisdom about the nature of life that may be revealed to people traveling on the shamanic path. This creation cosmology was perhaps best preserved in Germanic and Norse myths and stories. It was also documented by early Roman functionaries who traveled through Western Europe.

The meaning of word can also be understood through the image of a vast web of fibres, an image that appears frequently in early European literature and artwork. The European shamans visioned a web of fibres that flow through the entire universe, linking absolutely everything—each person, object, event, thought, feeling. This web is so sensitive that any movement, thought, or happening—no matter how small—reverberates throughout the entire web. In some of the incantations preserved in Anglo-Saxon manuscripts in the British Museum, the journey of the shaman’s soul into the otherworld is facilitated by a spider spirit. When an Anglo-Saxon shaman wanted to understand the complexity of forces affecting an individual, such as during initiations and healing, the shaman visioned the pattern of fibres entering the person.

I will never forget the first time I consciously experienced these fibres. One day in early summer, I was walking alone in a forest in England, enjoying the flowering wild bluebells that blanketed the ground between the oaks and beeches. Suddenly I sensed a pulsing in my body, around my navel, and I felt sick. At first I thought I would vomit, so I stopped and leaned against a tree. Then I saw hundreds of lines of light coming silently and beautifully from all directions and passing through my body. They were like shafts of golden sunlight filtering through the trees, only they were coming from every angle. The image was so clear and strong that I started to follow some of the lines of light, walking right into them and along them. They seemed like warm fibres supporting me, and I felt as if I were walking on air. The longer the experience lasted, the more wonderful I felt. After a time, I lay down on the ground and went to sleep among the bluebells. When I awoke, the sensation had passed. I now know that this experience was only an introduction to fibres, and that working with them involves not only sensory experiences but also ways of balancing life with their help.

Allen-Coombe: Anglo-Saxon shamanism flourished over a thousand years ago. What made you decide to explore that once-forgotten shamanic path?

Bates: During the 1970s, my spiritual quest led me to become deeply involved with Zen and Taoism. However, despite the fact that I admired these traditions very much, I felt handicapped by my unfamiliarity with the cultural backgrounds—the mythology, imagery, and physical landscapes—which gave birth to these visionary paths. I decided that I needed to find a Western or European approach. When I met Alan Watts, whose writings had inspired my journey into the Eastern traditions, he encouraged me in my search to discover a Western parallel to these great Eastern paths.

Of course, such life decisions are rarely intellectual ones. In retrospect, I can see that my path into Anglo-Saxon shamanism actually started during my childhood. From four up to about nine years of age, I had many recurring dreams involving wolves and eagles. As a child, I had an especially vivid imagination and I occasionally experienced visions, some during illnesses. These experiences haunted my life and propelled me inwards to the imagery of the unconscious. In the small, traditional village where I grew up, the adults were fairly accepting of my inner world. Later, when I moved to a city, I found that most people were locked into the material world and had little time for the inner life, so I learned to be much more careful about sharing my dreams and visions. Without my knowing it, however, these early experiences had sensitized me to the way of the Anglo-Saxon shaman.

It has often struck me that most paths to wisdom—the ways that enable us to move forward in life—usually involve going “back” to the realm of inner experience. Most of us had vivid inner lives as children, but we soon learned to deny those realities, in favor of the consensually validated “real world.” Following the shamanic path involves reentering the image world we knew as children and returning to that source of wisdom which, as adults, we have forgotten.

My quest to find a Western path led me first to learn about the Druids. Contemporary British Druids have a well-developed approach to spirituality which reflects a deep reverence for the landscape and the sacred forces of nature. They look to the ancient Druids of two thousand years ago as a source of inspiration, although they do not claim direct descendence from them. Because my goal was to find a path that was well rooted in the ancient Anglo-Saxon and Celtic ways of wisdom, I set out to find historical documentation on the original Druidic beliefs and practices but soon became frustrated by the paucity of available material. Although I have a lot of respect for contemporary British Druids, I realized their path wasn’t for me.

I then spent two years studying alchemy, both theoretically and practically. The alchemical practices include many meditative rituals focused on processes of inner and outer transformation. These practices taught me how to be sensitive to inner change, how to observe the workings of the psyche in response to archetypal imagery, and how to use external objects and interactions as metaphors for internal work. However, as an esoteric magical system, alchemy failed to address my primary concerns—the practices of healing and divination.

Eventually I became involved in the path of Wicca, or Witchcraft. I was fortunate to be able to study with some remarkable women, who taught me many things that would be important for my later understanding of wyrd. In the process of researching the historical roots of Witchcraft, I came across a reference to Lacnunga, an obscure one-thousand-year-old manuscript in the British Museum (ms Harley 585)

Lacnunga is essentially the spell book of an Anglo-Saxon shaman. It contains a collection of magical healing remedies, rituals, and incantations. Historians estimate that the document was written by Christians in the tenth or eleventh century, although the material had probably been passed down orally for several hundred years, from the pre-Christian era. At that time, writing was the almost exclusive province of Christian monks and missionaries, and it was extremely unusual for a collection of indigenous pagan shamanic healing spells to be written in the Anglo-Saxon vernacular. Because of the pagan nature of the material, historians speculate that the manuscript was written by a scribe or novice, and not by a monk.

Through research, I learned that portions of Lacnunga had been translated by Anglo-Saxon scholars, but that there had been very little analysis of the manuscript’s overall content and meaning. I eagerly made arrangements to examine the original document in the British Museum. Lancing is a beautiful book—a small, thick manuscript on vellum leaves, wit little diagrams and drawings carefully scratched into the margins to indicate the end of one spell and the beginning of another. Although most of the entries were magical healing remedies and herbal treatments, I discovered among them some rituals for shamanic initiation and training. I immediately recognized the manuscript as a shaman’s handbook—a touchstone for entering the world of the ancient European shaman.

I became tremendously excited, personally and professionally, at the prospect of breathing life back into the practices described in Lacnunga. The manuscript literally changed my life, as I took on the challenge of rebuilding the practice of wyrd through an experiential, as weak as scholarly, approach.

I soon found that evidence for the way of wyrd is substantial, but that it is widely scattered in books, journals, manuscripts, and museums throughout Europe. One of my tasks over the years has been to pull together all this information and integrate it. The process is rather like weaving a tapestry, only the materials are facts and ideas, image and stories. I have consulted countless journals and books in subjects as diverse as the history of medicine; Anglo-Saxon, Celtic, and Germanic social history; Icelandic sagas; comparative mythology; folklore studies; archaeology; and philology.

My research has showed that although there were some differences in details of expression between the Anglo-Saxons and the Celts—the two major cultural groupings in early western Europe—there was much overlap between the shamanic practices of these peoples. The shamans served as healers, diviners, spell casters (particularly through the use of the magical languages of runes), leaders of sacred rituals and celebrations, custodians of tribal wisdom, and advisors to warriors and chieftains.

After several years of studying research material in order to understand the system of shamanism represented in Lacnunga, I decided to explore some of the healing rituals presented in the manuscript and to recreate the journey described in its incantations and narratives. My work included practicing meditations, memorizing the stories, and journeying—physically into forest landscapes at night and psychically into visionary landscapes.

From the start of the project, my aim has been to reempower the way of wyrd as a living shamanic path. Throughout this process, I have tried to maintain absolute integrity, so that readers and workshop participants can see exactly how the historical material is being used. For that reason, I have included in the bibliography of The Way of Wyrd well over one hundred references to the most accessible material, so that readers can explore the sources for themselves.

Allen-Coombe: In The Way of Wyrd, you present Anglo-Saxon shamanism through the fictional experiences of Wat Brand, a Christian scribe who apprentices to a pagan sorcerer. Why did you choose this format?

Bates: Originally I had intended to write a nonfiction book that would explain the nature of wyrd, but my first attempts failed to bring the wonderful material to life. I then decided to use the format of a fictional story in the hope that it would speak more directly to the imagination that to the intellect. I felt the readers would be better able to experience something of the nature of the shamanic quest if I told the story through one person’s journey into the way of wyrd.

While conducting my background research, I had studied a historically documented mission from Anglo-Saxon England, and I decided to use this setting for depicting someone’s initiation into the way of wyrd. I had learned that when Christian missionaries traveled into pagan areas of Europe, they often sent a junior member of the mission to journey through the countryside, gathering information about the rituals, beliefs, and practices of the indigenous shamans. Since a scribe called Wat Brand had actually lived at the mission I studied, I gave his name to the fictional scribe in my book. The Way of Wyrd describes Brand’s experiences in gaining the knowledge of wyrd, and his initiation by a shaman called Wulf.

In preparing the book, I wrote a series of essays for myself on fifty or sixty different aspects of the principles and practices of wyrd, based on my experiential studies and the historical evidence available about the European shamanic path. The actual structure of the book and the unfolding of Brand’s quest were dictated by these accounts of my research.

allen-Coombe: In your book, you describe an individual’s life as “ a cloth woven on a loom.” What relevance does this image have to contemporary life?

Bates: Contemporary psychological science teaches us to image our lives and psyches in terms of a machine—in particular, a computer. Although that model bears little relation to the organic, living, breathing reality of the human experience, we continue to make educational, professional, business, medical, and military decisions as though the computer model were a close fit to our reality.

In contrast, Anglo-Saxon shamanic cultures viewed each person’s life experience as an artistic pattern evolving on a loom. The motif of goddesses spinning individual fates appears many times in the spells and stories which have survived and is one of the best-documented aspects of Anglo-Saxon shamanism. Admittedly, images of spinning and weaving were more familiar in those eras, but the use of a creative rather than mechanical metaphor is worth studying—especially when considering how to change our lives. Instead of changing our “life program,” we can change our “life design,” using metaphors of color, shape, texture, pattern, and theme.

Becoming sensitive to the fibres that pulse and reverberate within our lives is an important practice of the way of wyrd. Sometimes, in contemporary word healing workshops, we paint images of the fibres penetrating our lives, starting with those influences of which we are consciously aware—people, evens, hopes, and fears—and then moving on to fibres which can be perceived only through meditation and inner visioning.

Even if you are highly motivated to change your overall life pattern, you can’t just change it immediately, as if inserting a new program into a computer—to do so would be to break your life. You can’t afford to lose the strength inherent in what you’ve already got. You can alter the pattern, expressing previous themes in new and different ways, but developing a new pattern must be accomplished harmoniously, in tune with the energies that created the original design. Therefore, when working with individuals who want to make changes in their lives, we help them to get a clear picture of their existing life patterns, and then we guide them to redesign tose patterns through use of artistic media.

One man I worked with had many psychological blocks to deal with. He had undertaken conventional psycho-therapy but still felt confused and paralyzed by the multiplicity of his problems. So, before delving into the content of his individual issues, we simply mapped them out until he saw an overall pattern to his life. Then he expressed that patter through artwork and dance, creating a map of his psychological states.

We first choreographed a dance sequence that expressed his past psychological states and then choreographed a ritual dance that enabled him to transcend his blocks. The first time that he performed the entire dance was a tremendous cathartic experience for him. Each subsequent time served as a centering process, allowing him to reach a state of presence within himself, and was a ritual act of faith in his liberation. Of course, life issues are complex and need to be addressed in detail, but this process provided him with a bird’s eye view of his situation, allowing him to get his bearings. The improvement in his general well-being was remarkable.

Allen-Coombe: Much of Brand’s work in The Way of Wyrd deals with developing personal power. What is power in the Anglo-Saxon tradition, and how can people develop this kind of power?

Bates: In modern society, the concept of power has been debased—it is usually conceived of as power over other people. But in the European shamanic sense, power something that one ha within oneself. It is an enabling power which helps people resist being “overpowered” by others.

Forming relationships with guardian spirits is one practical way to nurture shamanic power. There are many accounts in European literature of shamans transforming into their guardian animals, both spiritually during initiations and ritually during celebrations and healings.

An important aspect of shamanic work is finding externalized forms—such as creatures, animals, or runes—that to only represent but give manifestation to one’s inner resources and strengths. The process has parallels with contemporary creative psycho-therapies in which a personal issue is given form through something external, such as a painting or sculpture. Even though we know the issue is “inside,” we seem to be better able to deal with it once it is transferred onto something “outside.”

One of the central premises of word is that, in certain states of consciousness, the boundaries between inner and outer realities become permeable and can be transcended. By working with guardian animals, we can get in touch with abilities that were formerly outside our awareness. For example, guardian spirits can give us access to many of those abilities that society has labeled “paranormal.” By embodying the fibres of word that reverberate through us, guardian animals can help us develop enhanced sensitivity to the myriad influences which constantly affect us but remain beyond the scope of our physical senses.

One way that I work with individuals is to help them connect with their guardian animals. Many people may be familiar with similar practices—where images of animals are induced and those animals danced—taught in short-term workshops. however, in contemporary word shamanism, we go much further in contacting this deep source of inspirational energy.

We begin by asking people to record animal dreams that they remember from childhood—nearly everyone has had them. Then we guide individuals on imaginal journeys to meet their guardian animals. That’s where the real work in word begins—people research their animals, observe them in the wild if possible, paint them, write stories about them, and work with them experientially and dramatically. This process is very personal and important, not something to be rushed. Some people training in word shamanism find that guardian animal work becomes a quest of high degree—a sustained path of exploration that illuminates many aspects of their lives.

Allen-Coombe: Dwarves and giants play a significant role in The Way of Wyrd. Can you discuss these beings and their relevance to shamanic practices?

Bates: Giants and dwarves featured significantly in the initiatory visions of Anglo-Saxon and Celtic shamans, as may be seen in the accounts of shamans’ journeys to the upper world and underworld. They also play a role in some incantations in Lacnunga, but they are given particular prominence in shamanic vision quest stories in the Norse sagas.

Later, under the influence of Christianity, the indigenous Celtic and Anglo-Saxon spirits were redefined as angels or devils. Eventually, the shamanic imagery was preserved only in stories for children, where it could be dismissed as fantasy.

In pre-Christian European shamanism, giants were embodiments of the elemental forces that had created the universe, and they represented tremendous, unbridled power. Stories related that giants had both knowledge and wisdom, but—as giants were often aggressive—this knowledge could only be gained by the shamans at great personal risk.

Dwarves were the powers that transformed the elements of the universe into material form. In early European cultures, blacksmiths were associated with dwarves and magic because of their ability to transform the basic elements of Earth into tools, weapons, and jewelry. when shamans journeyed into spiritual realms, they often encountered sacred smiths, usually imaged as dwarves, who made unbreakable swords and knives, and beautiful jewelry with magical properties. these dwarf-smiths were also responsible for transmuting the body, mind, and soul of the apprentice into that of the shaman.

In our workshops, we work to activate the dwarf powers of transformation inherent in our lives. First, participants tell and enact stories of the dwarf powers that they know form European mythology. Since over the centuries most of these stories have been altered and turned into children’s moral tales, we examine and reentrant the stories in their original shamanic versions. then we recast the stories in terms of our own lives, putting these “dwarf energy” aspects to work for our personal transformation.

To ritually enact our own transformational tales, particularly within a group, is a remarkable experience. Many people discover that story details they had forgotten become manifest as the experiences are given magical power. It is not psychodrama as we know it in contemporary psychotherapy but rather an infusion of transformational energy into those important life experiences which have not been resolved or celebrated—or, even worse, which have been locked into our psyches by denial or the wrong kind of analysis. This work often involves some suffering and sacrifice, but it ultimately creates beautiful, magical things from the elements of our lives—just as the dwarves made beautiful, magical things from Earth’s elements.

Allen-Coombe: In The Way of Wyrd, Wulf teaches Brand about the shamanic use of runes. Can you tell us about runes and other methods of communication with the spirit world?

Bates: In recent years, many people have become familiar with the use of runes as an oracular system. Runes were much more than an alphabet of angular shapes; they were an important form of sacred communication in the way of wyrd and were used with great respect and reverence. Runes were traditionally carved into wood, rock, or occasionally bone, or into metal jewelry and weaponry. the process of carving runes was a way of centering, meditating, and communicating with Earth. The carving of runic messages to the spirit world was an integral part of most healing and divining rituals.

Contemporary work in the way of word includes the use of runes as an oracle. Of course just as with other divinatory tools, the power inherent in their use depends upon the sensitivity, skill, and journeying capacity of the person who is doing the reading.

There are many ways of getting in touch with the other realms, and all shamanic cultures employ ritualized and sacralized means of communication with spirit forces. Some cultures use dancing, drumming, and chanting; other use painting or creating sacred objects. In the European tradition, advanced shamans often traveled with trained drummers and chanters, who performed sound rituals to aid the shamans in communicating with the spirit world during healings and other sacred ceremonies. There is a manuscript description from about one thousand years ago of a North European shamans who traveled with thirty trained chanters—fifteen men and fifteen women.

Allen-Coombe: Were there very many Anglo-Saxon shamanesses?

Bates: A thousand years ago, when shamanic traditions thrived in Europe, male and female practitioners were equally prominent and were accorded equal status. They performed some functions in common, although other tasks were divided along gender lines. For example, women had authority over rituals dealing with childbearing and were specialists in divination—in reading the future of individuals, communities, and the landscape.

In Anglo-Saxon shamanism, both male and female shamans practiced healing and presided over spiritual rituals of various kinds, although usually separately. Men followed a male path of initiation and women followed a female path, but both paths had equal status. Entering the shamanic world of the other gender was considered an advanced form of shamanism. Those shamans who were able to acquire elements of the wisdom, techniques, and insights of the other gender were the most highly admired.

When Christian missionaries came to western Europe, they presumed that the indigenous spiritual structure was vested in the male shamanic advisors to the tribal leaders. Ignoring the role of female shamans, the missionaries concentrated on persuading the chieftains to outlaw male shamans and replace them with Christian monks and priests Consequently, although the male shamanic path was quickly driven underground, the female shamanic path continued to flourish for several hundred years. However, in order to control the still-thriving shamanic approach to life, the Christian authorities eventually turned their wrath against the female shamans and instigated the infamous witch hunts.

Allen-Coombe: What shamanic tools would Anglo-Saxon shamans typically carry with them?

Bates: Probably the most important tool of a European shaman was his or her staff. These staffs were carved with runic inscriptions and decorated with metalwork and objects of symbolic significance.

Norse sagas from over a thousand years ago describe shamanesses in northern Europe carrying staffs decorated with ornate stonework. Among other uses, these power staffs enabled the shamanesses to journey to spirit realms. The image in popular culture today of witches flying on magical broomsticks may have evolved from stories of these magical staffs.

European fairy tales are replete with wizards carrying magic wands and staffs imbued with healing powers. Today, we dismiss these stories as fantasy, but there is evidence that the shamans’ staffs were used physically during rituals to draw sacred circles on the ground and to heal people.

In the way of wyrd, most healing, divination, and initiation rituals involved creating circles for containing and concentrating the flow of life force—physical, psychological, and psychic energy.The use of circles is well documented in Anglo-Saxon and Celtic literature and artwork. Even Anglo-Saxon jewelry—rune-cut armoring, and torcs worn around the neck—was used to aid in concentrating power.

As in many other cultures, the shamans of Europe usually performed in ritual costumes that were representative of their power animals—their sources of inspiration. There are numerous literary descriptions of European shamans wearing costumes decorated with feathers, stones, and other magical objects.

In researching ancient texts recorded by medical historians, I also came across several references to shamans working with seeing stones. These stones, usually marked with a shape resembling an eye, were used by shamans to see into the spirit world and to vision the spirit state of a person during healings and initiations.

the first time I personally encountered a seeing stone took place during a workshop I was leading in the Alps. Our group was standing under a huge beech tree with gigantic exposed roots, clinging to the thin soil of the Swiss mountainside. Just as I was telling the group about seeing stones, I saw among the roots a brown and pink stone, with an exposed, white area in the shape of an eye. When I picked up the stone, it fit smoothly into my palm. My whole body began to tingle, and I immediately knew it was a seeing stone. I have since used it many times to read a person’s energies. The stone creates a channel of sight which allows me to vision a person’s fibres and energy channels, rather than his or her physical form.

Allen-Coombe: Can you tell us more about shamanic healing in the Anglo-Saxon tradition?

Bates: The historical basis of my understanding of wyrd healing comes primarily from Anglo-Saxon manuscripts in the British Museum and from some smaller manuscripts housed in various other European museums. These “medicine work handbooks” provide a picture of the healing practices used in western European shamanic traditions.

Typically, healings started with a spirit reading of the patient. This reading would be carried out either by using seeing stones or by drumming and chanting until the shaman had a vision revealing the path to be followed in the healing. The healing process often involved “singing the patient better”—using an incantation to create a healing word web for the patient. The incantation, sometimes created specifically for that patient, induced imagery within the patient’s mind that catalyzed mind/body healing. Of course, the incantation also enlisted the assistance of the spirits and activated healing forces from the web of wyrd.

Sometimes it was believed that the patient had been possessed by harmful spirits , and the shaman then had to drive these sickness spirits away. This work required great care, because confronting dark spirits could be dangerous even for an experienced shaman.

In some cases of serious illness, it was believed that the patient had lost his or her soul. Lancing contains several incantations for journeying in search of lost souls. It was usually assumed that the soul had been stolen for a particular reason, or a combination of reasons, that had to do with the way the patient had been living his or her life. So, as step in retrieving the soul, the shaman had to find out why the person’s soul had been stolen and who in the spirit realm had stolen it.

In our contemporary wyrd practical healing work, the shaman’s job also includes helping individuals reweave their lives into a form which develops their strengths and protects their souls.

Allen-Coombe: What relevance does the way of wyrd have today?

Bates: I consider wyrd to be as relevant and powerful now as it was for our Anglo-Saxon ancestors. Although our ancestors lived in a technologically simpler world, they were more sophisticated in spiritual matters than we are. We can learn from their wisdom, because they dealt with the same matters of mind, body, and spirit that we are still grappling with today. It’s important to remember that—although our physical and cultural environments have evolved greatly over the last few centuries—our deep inner nature has probably not changed much over the last several thousand years.

I also believe that the shamanic path can play an important role in solving crucial personal, social, and global issues that confront us today. Although the ritual forms of shamanism needed to solve today’s problems won’t necessarily be identical to those that flourished in traditional hunting or agricultural communities, the holistic vision of wyrd and many of its ancient shamanic elements—its concepts of life force, spirit guardians, and interconnecting fibres; its healing techniques; and its approaches to life and death—are still directly applicable to our lives.

the basic message of The Way of Wyrd is that we can recapture and revitalize a shamanic approach to wisdom that is based on Anglo-Saxon and Celtic traditions. In reading about wyrd, many people have a sense of recognition—a sense that it’s al something they already knew, deep down, but had forgotten. The way of wyrd is the archetypal shamanic wisdom of the European peoples. I would like to see this heritage take its place alongside the other great traditions of spiritual liberation, for anyone to learn from.

Allen-Coombe: What are your plans for the future, particularly in regard to your research work?

Bates: Recently, my personal research efforts—both scholarly and experiential—have been concentrated mainly on the processes of initiation and on the roles of male and female paths through the shamanic realm. I am currently compiling this material—as well as my findings in other areas of word shamanism—which I plan to work into a number of new books.

Moreover, since The Way of Wyrd’s publication in Europe, I have met many remarkable people who—without being knowledgeable about their European shamanic heritage—have been exploring shamanic practices in their own lives. Because I believe that it is very important to encourage the exploration of shamanic practices in nontraditional settings, where there is little cultural support for the role of the shaman, I am writing a book about some of these encounters.

The response to The Way of Wyrd has been very strong in Europe and has enabled me to creat the experiential Shaman Research Project at the University of Sussex. The project is an unusual enterprise for a university, because our aim is not merely to build academic knowledge of a historical form of shamanism but to explore Anglo-Celtic shamanism at an experiential level. We now have six researchers directly involved in the project, and part of our work includes studying aspects of shamanism from other traditions around the world. We are also setting up a worldwide network of people who wish to be connected with the project on a regular basis. Ongoing research includes work on guardian animals, masks, masculine and feminine shamanic paths, sacred landscapes, and shamanic performance.

My overall aims are to recreate and reentrant the wisdom inherent in European shamanism and to apply its practices to personal development, psychotherapy, and healing, as well as to the broader issues of the environment, education, and the arts. I am interested in seeing that the insights of shamanism are introduced into as many appropriate settings as possible. This work is in its early stages, and I hope that I shall be able to report our progress widely as the project unfolds. It is time for the way or wyrd to take its place alongside the other great shamanic paths, so that its traditional wisdom can help us face the future.

Janet Allen-Coombe is a research psychologist at the Shaman Research Project, University of Sussex, and is currently writing a doctoral dissertation based on her research on guardian animals.

Brian Bates may be reached at the Shaman Research Project, Arts Building B, University of Sussex, Falmer, Brighton, Sussex, England BN1 9QN

An Excerpt from The Way of Wyrd by Brian Bates

“Do you really believe that you can read future events from a tiny snatch of bird flight? Do all your people believe in such omens?’

Wulf rolled on to his back and cupped his hands behind his head, squinting up at the sky.

‘Omens frighten the ordinary person because they believe them to be predictions of events that are bound to happen: warnings from the realms of destiny. But this is to mistake the true nature of omens. A sorcerer can read omens as pattern-pointers, from which the weaving of word can be admired and from which connections between different parts of patterns can be assumed.’

I was puzzled by his use of the term ‘wyrd.’ When used by monks orating poverty, it seemed to denote the destiny or fate of a person. I explained this view to Wulf and he hooted with laughter, sending the sparrows flapping from the shrubbery in alarm.

‘To understand our ways, you must learn the true meaning of wyrd, not the version your masters have concocted to fit their beliefs. Remember that I told you our world began with fire and frost? By themselves, neither fire nor frost accomplish anything. But together they create the world. Yet they must maintain a balance, for too much fire would melt the frost and excessive frost would extinguish the fire. but just as the worlds of gods, Middle-Earth and the Dead are constantly replenished by the marrying of fire and frost, so also they depend upon the balance and eternal cycle of night and day, winter and summer, woman and man, weak and strong, moon and sun, death and life. Thee forces, and countless others, form the end points of a gigantic web of fibres which covers all at the worlds. The web is the creation of the forces and its threads, shimmering with power, pass through everything.’

I was astounded by the image of the web, which seemed to me both stupendous and terrifying. I trembled with excitement, for I knew that Eappa1 would drink in such information like a hunter pinpointing the movements of his prey.

‘What is at the centre of the web, Wulf? Are your gods at the centre?’

Wulf smiled, a little condescendingly I thought.

‘You may start at any point on the web and find that you are at the centre,’ he said cryptically.

Disappointed, I tried another line of questioning. ‘Is word your most important god?’

‘No. Wyrd existed before the gods and will exist after them. Yet word lasts only for an instant, because it is the constant creation of the forces. Word is itself constant change, like that seasons, yet because it is created at every instant it is unchanging, like the still centre of a whirlpool. All we can see are the ripples dancing on top of the water.’

I stared at him in complete confusion. His concept of wyrd,obviously of vital importance to him, repeatedly slipped through my fingers like an eel. I went back to the beginning o f our conversation.

‘But Wulf, you say that the flight of birds shows you the pattern of wyrd, of these fibres; if you can predict events from wyrd, it must operate according to certain laws?’

Wulf looked at me with kind, friendly eyes. He seemed to be enjoying my attempts to understand his mysterious ideas.

‘No, Brand, there are no laws. The pattern of word is like the grain in wood, or the flow of a stream; it is never repeated in exactly the same way. But the threads of word pass through all things and we can open ourselves to its pattern by observing the ripples as it passes by. When you see ripples in a pool, you know that something has dropped into the water. And when I see certain ripples in the flight of birds, I know that a warrior is going to die.’

‘So wyrd makes things happen?’

‘Nothing may happen without wyrd, for it is present in everything, but word does not make things happen. Wyrd is created at every instant, and so word is the happening.’

Suddenly I tired of his cryptic responses. ‘I suppose the threads of wyrd are too fine for anyone to see?’ I said sarcastically.

Wulf chuckled goodnaturedly. ‘Sometimes they are thick as hemp rope. But the threads of wyrd are a dimension of ourselves that we cannot grasp with words. We spin webs of words, yet wyrd slips through like the wind. the secrets of wyrd do not lie in our word-hoards, but are locked in the soul. We can only discern the shadows of reality with our words, whereas our souls are capable of encountering the realities of wyrd directly. This is why wyrd is accessible to the sorcerer. the sorcerer sees with his soul, not with eyes blinkered by the shape of words.’

I knew Wulf’s views to be erroneous, yet I was fascinated by them. He spoke about his beliefs as confidently and fluently as Eappa explaining the teachings of our Savior. I rested my chin on my hands and tried to analyse Wulf’s ideas as Eappa would have wished. ‘Be sure you understand clearly everything you see and hear,’ he had cautioned. ‘You can remember only what you comprehend.’ I tried to identify the main tenets of Wulf’s beliefs and subject them to scrutiny, one by one.

Wulf leaned closer to me and spoke into my ear as if sharing a secret:

‘You are strangling your life-force with words. Do not live your life searching around for answers in your word-hoard. You will find only words to rationalize your experience. Allow yourself to open up to wyrd and it will cleanse, renew, change and develop your casket of reason. Your word-hoard should serve your experience, not the reverse.’

I turned on him in irritation. ‘I was chosen for this Mission because I do not swallow everything I hear like a simpleton. I am at home in the world of words.’

He smiled gently. “Words can be potent magic indeed, but they can also enslave us. We grasp from wyrd tiny puffs of wind and store them in our lungs as words. But we have not thereby captured a piece of reality, to be pored over and examined as if it were a glimpse of wyrd. We may as well mistake our fistfuls of air for wind itself, or a pitcher of water for the stream from which it was dipped. That is the way we are enslaved by our own power to name things.’

‘My thoughts are my personal affair,’ I said sulkily. I was here to listen to his beliefs, but not to submit to criticism of my private contemplation.

‘Thoughts are like raindrops,’ he persisted, introducing yet another of his interminable images. ‘They fall, make a splash and then dry up. But the world of wyrd is like the mighty oceans from which raindrops arise and to which they return in rivers and streams.’

Editor’s Note

Brother Eappa was Wat Brand’s teacher at the Mercian Monastery, where Brand served as a scribe. As part of his efforts to establish a mission at the Saxon court, Eappa sent Brand to “travel though the kingdom, gathering information on the beliefs and superstitions of the heathens.”

From The Way of Wyrd by Brian Bates

Copyright 1992 by Brian Bates